Hawaii hosting major esports tournament

The U.S. professional football season is just getting underway, but the international esports scene is heading into a grand finale this week... in Honolulu.

While it may be a stretch to call it the Superbowl of esports, the Overwatch League is kicking off its 2021 Overwatch League Playoffs at the University of Hawaii on Saturday, with the finals set for the following Saturday, Sept. 25.

This unique and significant opportunity comes after UH successfully hosted a mid-season, trans-Pacific tournament in May, hosting qualifying teams from Dallas and Florida in the U.S. and Shanghai and Chengdu in Asia.

Whither esports?

If you haven't been paying attention to professional esports, we've come a long way from LAN parties in musty internet cafes. As your kids and grandkids will tell you, esports is big business, rivaling traditional, ball-based sports.

The first Overwatch League Grand Finals in 2018.

All the trappings are there, from aggressive recruiting to college scholarships (including in Hawaii), from big paydays to sold-out arenas full of screaming fans, from celebrities and scandals to, of course, investors and venture capital.

Esports is a massive, and growing, global industry, said to be worth $1 billion today, and perhaps twice that by next year.

Despite being thousands of miles from any other major city, and despite "playing on a hawaii server" being a gamer joke for handicapped play, it turns out the Aloha State has lots to offer and a lot of opportunity in the esports world.

What is Overwatch?

Overwatch is one of the biggest video games in the world, with over 60 million players and raking in over a billion dollars in in-game spending. (Sales of a pink skin, or virtual outfit, raised $12.7 million for breast cancer research alone in 2018.)

Overwatch is categorized as a team-based shooter, or "hero shooter," with six-on-six competitive matches.

The Overwatch League is organized by Blizzard, which publishes the game (and its sequel, Overwatch 2) and describes it as "the first major global esports league with city-based teams."

While watching other people play video games may sound dull (or at least less interesting than watching other people play with balls), esports tournaments today are elaborate, raucous, brilliantly produced contests that fill stadiums and arenas and rival many sports championships.

Before the pandemic, anyway.

Esports in the time of COVID

COVID-19 put a swift end to in-person esports events in 2020, and sadly 2021 turned out to be no less merciful to those hoping to join cheering crowds in a major city.

Game publisher Riot Games, which makes League of Legends and Valorant, decided to move its events to Reykjavik, Iceland in May. Overwatch, meanwhile, officially canceled its in-person events last month, also leaving audiences only able to watch online.

But they'll be watching players on the UH Mānoa campus.

How did this come to be? I went straight to the source: Nyle Sky Kauweloa.

Sky says

Sky is a communication and information sciences PhD student, head of the UH Mānoa Esports Task Force in the College of Social Sciences, and instructor. The focus of his studies, teaching, and passion is esports.

He made the connections that made Hawaii's hosting of professional esports possible, coordinating "Project Aloha," the successful May event that gave Blizzard the confidence it needed to bring its playoffs and finals back to Honolulu.

Even in the midst of the complex prep work needed for this week's events, Sky spent an hour with me to share some of the personal and professional stories behind this esports milestone.

Q. I always thought esports in Hawaii was a nonstarter because of our distance from other tech hubs. Not so much internet speed but latency, the delay. By the time you saw the enemy, he had already shot you and done a little dance. What made you think this was even possible?

A. For many years, since I was doing esports research at the college level, I would visit colleges in Canada, Irvine, Chicago, and I wondered why we didn't have something like this in Hawaii. I thought we could probably do really well in it.

Island nations have played a unique role in esports in 2021. The two biggest esports league are Overwatch and Riot’s World Tournaments. While Overwatch was in Hawaii they held in-person team versus team finals in Iceland for similar reasons. They also had to move to Iceland for their Finals, just like Overwatch is returning here.

This is like the NBA, this is like the MLB, and they're not pivoting to traditional esports metropolitan hubs. They're not going to LA, they're not to Houston (where people ended up getting COVID during a tournament), they went straight to these isolated island locations.

All this time I’ve been doing research and promoting esports in Hawaii. For Overwatch to come to Hawaii is validation. I'm happy about it because it does open up Hawaii for publishers and developers, too.

Q: But what about the long distances and slow pings?

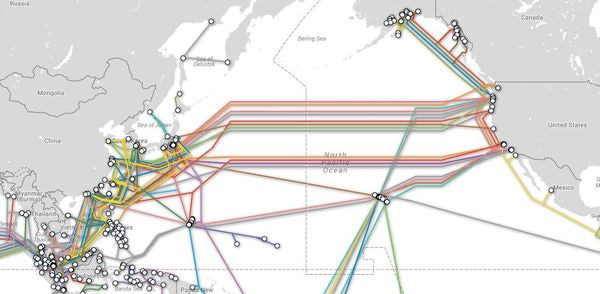

Pacific undersea cable network (circa 2016). See SubmarineCableMap.com.

Even though we’ve been chosen to host these events, it’s no way a sign that we’ve somehow solved the problem, or that we don't need more infrastructure and broadband access. We were chosen, selected, that’s a very big deal. That is a marker. But we still have a problem, and in some ways, this is an issue we can’t say we’ve moved past.

But Overwatch is unique. They surveyed the entire professional league and asked, "What’s the worse latency capacity you can play at?" The consensus was roughly 90 milliseconds.

That is quite shocking. It’s kind of unique to the game of Overwatch. It’s not as sensitive to latency as other games. You can’t play most games at a competitive level — Valorant, League of Legends — at 90 milliseconds.

One example. We had one player from Atlanta. Overwatch League has teams all over North America. The whole schtick is that we have them come to Hawaii, closer to Tokyo severs. But he had a medical issue, and didn't come to Hawaii. This player is one of the top players, and he was playing from Atlanta at roughly 200ms, and he was still winning.

When Overwatch contacted me in December 2020, I was shocked, but didn’t say no, because I wanted to figure out what our disadvantages were. I wanted to be told up front what’s wrong.

They came to Manoa, and we went down to the iLab. I knew we were going to have latency issues, and the first test was 120 milliseconds. Horrible, non-negotiable. It turned out Overwatch data was going from iLab, to the West Coast, then Chicago, then back to Tokyo. It was supposed to go direct to Tokyo.

The Information Technology Center (ITC) folks at UH were able to swing the data straight to Tokyo, and it went from 124ms to roughly 90ms. That’s a big drop. 90ms is hard to imagine for a global competition, but they were happy.

Q: So Hawaii was just good enough? Or were there other reasons Overwatch wanted to come here... besides the obvious reasons, I suppose?

Esports is a mediated activity via the Internet, but at elite levels, play is brought to one geographic location.

We always think of Hawaii as a bridge between East and West. That was the metaphor of generations past. Hawaii is also the middle node between two large continents, and that's still relevant when it comes to transmission rates and broadband connectivity.

Overwatch League really wants to have global esports. Every league is trying to attain that, but it doesn’t really exist. We have more like dominant continents or dominant regions: North America, Europe, Asia, Latin America. If you want global esports, that has to connect East Asia and North America.

How do you make that happen? You get as close as possible. Hawaii serves as a really interesting discussion point in how you get close as possible for competitive play, for fair play, in many ways tournament operators wish they could.

Q: Does that mean that playing in Hawaii is challenging in the same way to everyone? The latency is an equalizing force?

Yes, and leagues are doing it already. For example, if you have Hawaii playing off of the Tokyo servers versus Korea and China playing off those same Tokyo servers, that’s still unfair. Korea and China only have a short gap to fill.

Overwatch League has created a latency tool that equalizes it. Whoever has the worst latency sets the latency everybody plays on. All the South Korean and Chinese player have to play at our latency.

Q. So our location is good. What about our players? Can Hawaii-based teams be competitive globally?

That's one of the things that’s interesting about Hawaii. Hawaii players are robust as competitors because they have a flexible view of the environment in which they operate. I know many players who refuse to play if their latency is above 20ms. They get triggered psychologically. But Hawaii players are used to 80ms all the time, or worse.

I compare them to football players in Colorado. They do high altitude training, and when they go anywhere else, they’re happy. In soccer, some of the best players coming from Brazil. They grew up in dire straits, playing in the fields, rocky conditions, and thus have the capacity to deal with multiple challenges.

Whether esports performance, or sports performance, teams need to get players to be more flexible and robust in their environment.

But while the talent pool in Hawaii is good, I'm not sure we’re ready for a professional team. Most teams don’t scout locally, anyway. Dallas players are from South Korea, Florida players are from South Korea.

Q. How do our facilities stand up against other esports venues?

The UH Information Technology Center.

The biggest esports stadium is in Arlington. Yet Hawaii directly challenged Arlington this year. All the OWL events could have been happening here. We have advantages even against an esports hub on the mainland. Hawaii can play a role, and it doesn’t need to be a continuous thing.

But we are at capacity. The ITC building is an office building, and people need to work. We have a room right next to cubicles for workers. It's not an ideal location.

We just hosted two teams at a time in May, June, July, and August. Now, we'll be hosting five at one time. We'll be splitting teams between the iLab and ITC and have scout out the capacity of various rooms to split up people.

Q. And then there's COVID.

We're very strict with COVID protocols, and the league is too. Everyone had to be tested. Everyone in my internship, maybe 20 students, plus 10 staff, and the two teams, maybe 30 individuals.

Q. So if not UH, who else could host esports events?

The Athletics department was involved in these discussions early on, thinking maybe the Stan Sheriff arena, but they were confused by it. Now that we've run it, though, perhaps we could hand it off.

I've also been talking to people about building an esports arena in the Aloha Stadium entertainment district. And these don't have to be facilities only for esports. A 2,000 seat multipurpose, modular space for different events could work. And we would not just bring in mainland spectators, but from Asia as well.

We’ve done well. When Overwatch League came, it was simply a rental facility discussion. We said we could do more, and get students and the community involved. One of my goals is that this is a knowledge-sharing relationship.

Q: How have your students reacted to having Overwatch League on campus?

It’s been an interesting journey. Our students have had unprecedented access to how this league is run. In fact, in July, the Overwatch staff couldn’t make their flight to arrive on Monday for setup, so our students started the setup without the league. They had learned enough from May to do it by themselves.

One of the goals in my course, this semester, is to highlight Hawaii’s connections. Inviting speakers who played a pivotal role in shaping Hawaii’s scene. And I continue to find them in important parts of the industry: at Riot, Fortnight, a slew of other positions. At Overwatch League, their key graphics and content creator is from Kamehameha Schools. I ran into a woman running marketing for 100 Thieves from Maui.

We often view ourselves as on the edges of the periphery of global esports, but we play a much more central role.

Q: And in technology in general.

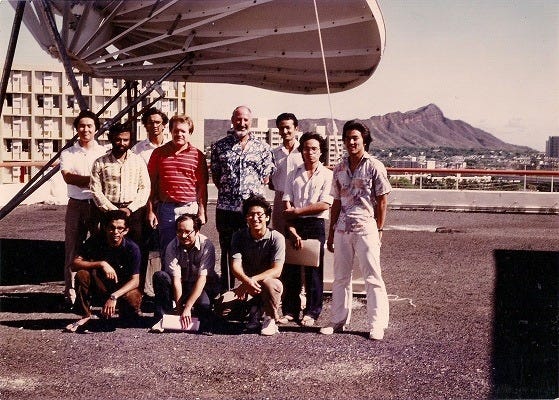

All wireless communications today utilize the ALOHA protocol.

We in Hawaii got used to communicating with the world via mediated communications from early on. Look at ALOHANET. We had to push technology forward for us to be a part of it. Hawaii played a very early role in the internet.

Now, Hawaii finds itself as a central location in global esports. I continue to see and say, what a shock, we keep finding Hawaii people in all these industries -- communications, internet, games.

Q. What would you say to non-gamer, non-technical, skeptical Hawaii residents about what esports means to Hawaii's students, businesses, and overall economy?

If people are confused or skeptical, I would say, that’s completely normal. This industry is so new, and changing so quickly. But while the tech industry is something that moves forward and pushes progress, it also draws from history constantly.

We always assume esports is completely immersed in technology, but we don’t think about how much is people skills and developing relationships. It requires a multitude of literacies. The jobs that are required to run a league are diverse. They require technical proficiency and skill but it's not all technical knowledge. Some of the biggest Overwatch League bigwigs come from political science, international relations, sales.

As for players? We have success cases there too.

Retired esports pro Dyrus is from Honolulu.

Dyrus, a Kalani alum, is retired now at the ripe age of 25. He’s an important case study. He grew up playing with the horrendous ping, but he was able to develop enough skill to move to LA to play with team house TSM. He's one of the founding godfathers.

We have a woman player, Kiara, who played for Dignitas in Europe. She loved it so much, she dropped out of high school — though I wouldn't recommend that — and she blazed this path in a time and an era when she had a lot of pushback and resistance. She's succeeded in spades.

Banner image: adamkaz/Getty Images