Got Encryption? Revisiting Privacy v. Security

President Obama wants to keep the country safe from cyber attacks. But will he chip away at privacy to do it?

The annual "State of the Union" address by the President of the United States isn't exactly blockbuster entertainment. It's a ceremonial exercise in constitutional rhetoric that ostensibly gives Americans an idea of how things are going, and what the administration wants to accomplish (at least if it didn't have to fight an opposition-run congress).

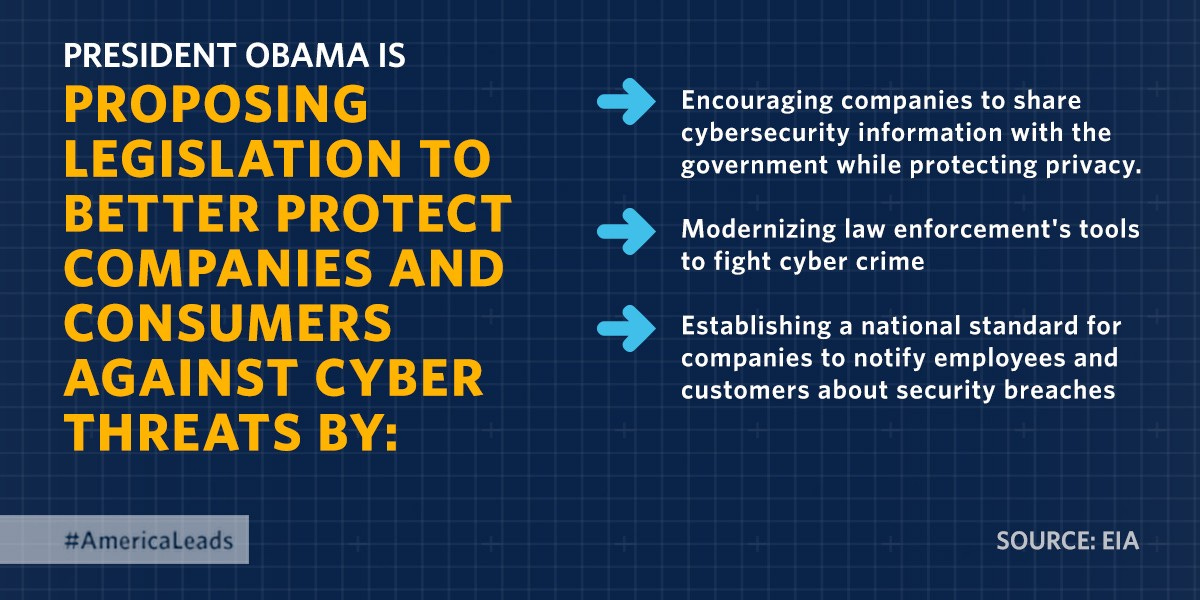

Rather than tuning in, many political wonks and geeks just wait for the text of the speech to be posted online. This year, the White House helpfully published the speech on Medium in advance, complete with ready-to-share graphics. With the text, it's merely a matter of searching for our favorite keywords. In my case, I was looking for clues as to his priorities when it came to "technology." Here was the key passage for 2015:

"No foreign nation, no hacker, should be able to shut down our networks, steal our trade secrets, or invade the privacy of American families, especially our kids. We are making sure our government integrates intelligence to combat cyber threats, just as we have done to combat terrorism. And tonight, I urge this Congress to finally pass the legislation we need to better meet the evolving threat of cyber-attacks, combat identity theft, and protect our children’s information. If we don’t act, we’ll leave our nation and our economy vulnerable. If we do, we can continue to protect the technologies that have unleashed untold opportunities for people around the globe."

As with most things in big speeches, it certainly sounds like a priority that everyone can agree on. But what exactly does President Obama mean when he says Congress needs to act to "combat cyber threats, just as we have done to combat terrorism"? Something like the Patriot Act?

It might seem like a stretch to think that our privacy might again be threatened, but the President's remarks come less than a week after he publicly backed British Prime Minister David Cameron in his demand for greater access to digital communications.

"Are we going to allow a means of communications which it simply isn’t possible to read?" Cameron asked. "My answer to that question is: ‘No we must not.’ Do we allow terrorists safer spaces for them to talk to each other? I say, 'No we don’t,' and we should legislate accordingly."

And after meeting with Cameron, Obama expressed his support for the idea. And the move comes after FBI director James Comey criticized tech giants like Apple and Google last fall for encrypting data in such a way that even Apple and Google, the makers of the technology, couldn't decrypt even if they wanted to. Obama said Silicon Valley tech companies are "patriots," and insisted that there must be a way to keep information secure... but made available to the government if deemed necessary.

It's not the first time the government has demanded a back door to encrypted systems. Back in 1993, the NSA suggested that manufacturers use their Clipper chip to scramble data, leaving the NSA with a master key that could unscramble messages in the name of national security.

As you might have guessed, it didn't exactly catch on.

Requiring backdoors into secure systems makes any system less secure. And if there is a master key, a master key can be abused, or duplicated, or stolen. After Prime Minister Cameron's latest remarks, Cory Doctorow noted that such built-in weaknesses would endanger every citizen and destroy the tech industry.

And as far as terrorists using encryption, they very well may. But analysis of nearly every major terrorism attack to date has shown that the problem isn't getting access to a critical piece of data, it's finding significant information somewhere inside the massive amounts of data that's already being collected.

Suffice it to say, while the handy infographic above calls for "encouraging companies to share cybersecurity information with the government while protecting privacy," that's something easier said than done. But if there's anything government has proven, it's that even bad, horrible, dangerous ideas can become law.

So what's a geek to do?

Well, you should certainly contact your congressional delegation and other government representatives to explain the importance of secure communications and privacy. After all, sometimes, geek voices are heard.

But the other thing I'd recommend is making the effort to use secure methods to communicate. Even if you've nothing to hide, there's no reason everything you do or say should be easily intercepted and recorded. The more "regular people" use encryption, the more security and privacy will become a default, rather than a geeky quirk.

There are a lot of tools out there, from Tor for private internet browsing to Silent Circle's encrypted phone calls and messaging. But a good, free, well-established place to start might be using PGP/GPG to encrypt and sign your email. I've been using it for years, and even blogged about it a couple of times.

Although there's a lot going on (you can read up on public key cryptography), all you need to know is that with PGP/GPG, you have a private key and a public key. Anyone with your freely-available public key can encrypt a message to you, but that message can only be decrypted with your private key (which only you have). With encryption at both ends, only you and your recipient will be able to decode a message... whether it's a planned corporate takeover, or your grandma's cake recipe.

Unfortunately, none of these tools are easy to use. I've gotten stuck more than a few times, and have gone months unable to decrypt a message because something broke along the way. But I still think it's important to try, play around, and even fail. These tools only get better, and will get better faster if more people are using (and periodically yelling at) them.

If you have a Mac, and you've never used PGP/GPG before, you should simply follow The Best PGP Tutorial for Mac OSX, Ever. With GPG Tools , the Thunderbird email cilient, and the Enigmail plug-in installed, you can start sending and receiving encrypted email in an afternoon. It goes faster if you create a new email address just for encrypted email exchanges, but it goes much slower if you want to use an existing email account or an existing private encryption key.

If you have a Windows machine, you will start with GPG4Win, but will get around to using Thunderbird and Enigmail as well.

Using PGP/GPG on mobile devices is still rough. There's iPGMail for iOS, but it was so clunky I almost gave up. On Android there's APG, but I've never used it.

Once installed, you basically need to fill your "keychain" with the public keys of people you want to exchange messages with. You can look them up on keyservers, or just ask for them (if you know the other person has one). You can find my key on the major keyservers, posted here, and even at Keybase.

(As an aside, Keybase is an interesting animal, trying to connect public-key crypto with social media. You could also start there, doing your encrypting and decrypting in the browser, but it can get hairy fast, unless you're into command-line interfaces.)

I'll be honest, though. I've used PGP/GPG since 1996. Over those nearly twenty years, I'd say I've exchanged a hundred encrypted messages, most of them with just a handful of people. That breaks down to about five messages a year, which is not a bustling inbox. But I'd still be delighted to correspond with you, whether to share state secrets or bad jokes.